We’re back with the next instalment in our fortnightly A–Z of Health Research Equity series – hoorah! If this is the first post you’re reading in this series, I’d recommend catching up with the introductory post and the first alphabet post: A is for Accessibility.

We’re now at the letter B, and this is a post I’ve been looking forward to writing since I first came up with the idea for this blog series. Today, I’m going to share some concepts and ideas that will help you understand our approach to inclusive and equitable health research at COUCH Health. Today, I’m talking about Biology.

Biology is a topic that comes up frequently when discussing diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in the context of health. This may come as a surprise, but I think it’s something that we as a community should be spending less time on. Let me explain…

What makes us healthy?

Our experience of health, and whether we consider ourselves ‘healthy’, is not purely a result of whether we exercise regularly, eat a balanced diet, and interact with the health system when we feel something is wrong. We can do all of the ‘right’ things and still experience significant ill health. This is because our health is shaped by a range of different factors, some biological, some interconnected, and many out of our direct control. Those factors that are out of our control tend to be the root cause of health inequalities.

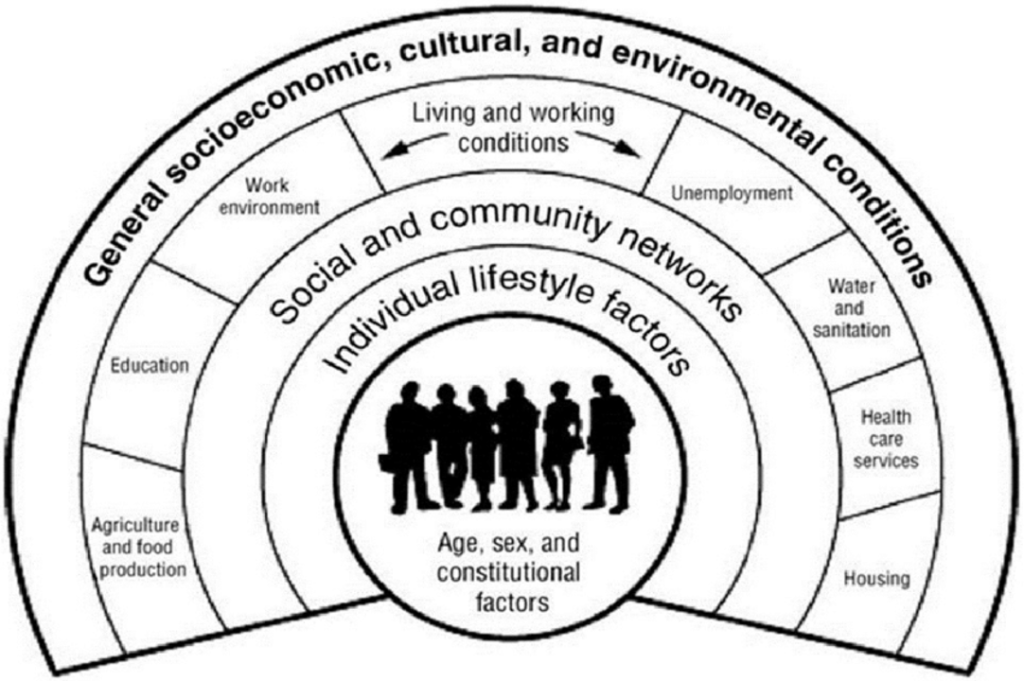

The infographic below was first published in 1991 and is known as the Dahlgren-Whitehead rainbow. It maps the relationship between the individual, their environment, and health, and gives you an idea of the breadth of factors we often don’t control. The model has been used by the World Health Organisation, Public Health England, the UK’s NHS, the US’s National Institute of Medicine, and many other global health partners. It remains one of the most effective illustrations of health determinants over 30 years after its release.

How does that impact health research equity?

We know that health is determined by a range of factors, including the individuals themselves and the environments within which they are based and interact. Things are slightly different when it comes to the conversations about health research equity, and DEI work more broadly.

Here, we usually focus on individual characteristics rather than their environments: age, sex and gender, ethnicity, socioeconomics, disability, neurodiversity, religion and belief, and sexual orientation. The reasons for this would require a whole blog post to themselves, but in broad terms, and in my experience, this is because it’s easier to think about immediate impact; what can we change now with these characteristics in mind?

We know we can’t change the health of people around the world overnight, so instead, we chip away at the problem, making health research more acceptable, more appropriate, and more accessible with every project we work on. On a personal note, making a conscious effort to think this way ensures that I don’t get bogged down with ‘ifs’ and ‘buts’, keeping me on track with impact and solutions in mind.

Biology and inclusivity

Now, I want to get to the nitty gritty of individual characteristics and unpick whether and how we should consider biology more deeply when thinking about improving health research equity. To do this, I’m going to focus on sex and gender, as they are often used interchangeably despite having different meanings.

Sex and gender

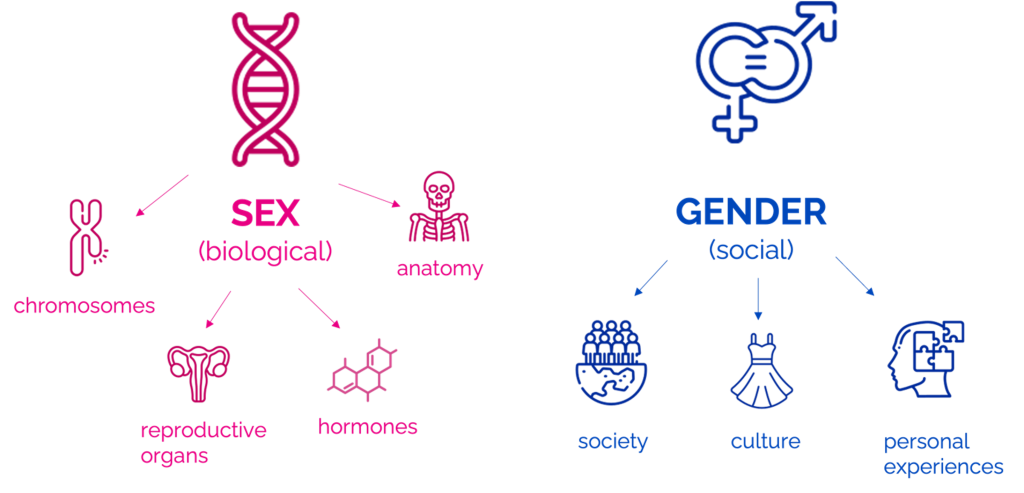

Sex and gender are among the main social determinants of health; in basic terms, sex is biological (chromosomes, reproductive organs, hormones, and anatomy), and gender is social (personal experiences, culture, and society).

There is good evidence to suggest that biology plays a role in health.

Take heart attacks as an example:

- Males are at greater risk of heart attack than females.

- On average, females have heart attacks seven to ten years later than men. Although the reasons for this are still under investigation, younger females are thought to be protected by oestrogen.

- After menopause, the risk of heart attack in females rises.

If you look at gender rather than sex, the situation gets more complex:

- People socialised as women typically arrive at the hospital later than men while having a heart attack.

- Trans people, whether they have medically transitioned or not, are at higher risk of heart attacks. The fact that this risk remains whether people have medically transitioned or not suggests that stigma and stress may be significant contributors.

It’s clear that both biology (sex) and society (gender) have an impact on health inequalities when it comes to heart attacks. It’s also clear that we cannot change people’s sex and their associated health inequalities.

We can’t change people’s gender, but we can change how society, the health system, health researchers, and clinical trial teams interact with people based on their gender.

We can educate people to ensure that women get to the hospital and receive treatment for heart attacks in a timely manner. We can work to limit the stigma, discrimination, violence and stress that trans people experience.

When you’re thinking about making health research more inclusive, I recommend thinking more deeply about the social, societal, and cultural influences at play. Biology is important, but I truly believe we will make change more quickly and with more impact if we remove biology from the forefront of our minds.

We are all human, and in order to make sense of the world around us, we have built social constructs. These have encouraged division and segregation, but just because these social constructs are real doesn’t make them true. We built them, and